Latest Posts

The Great Wealth Exodus of 2024

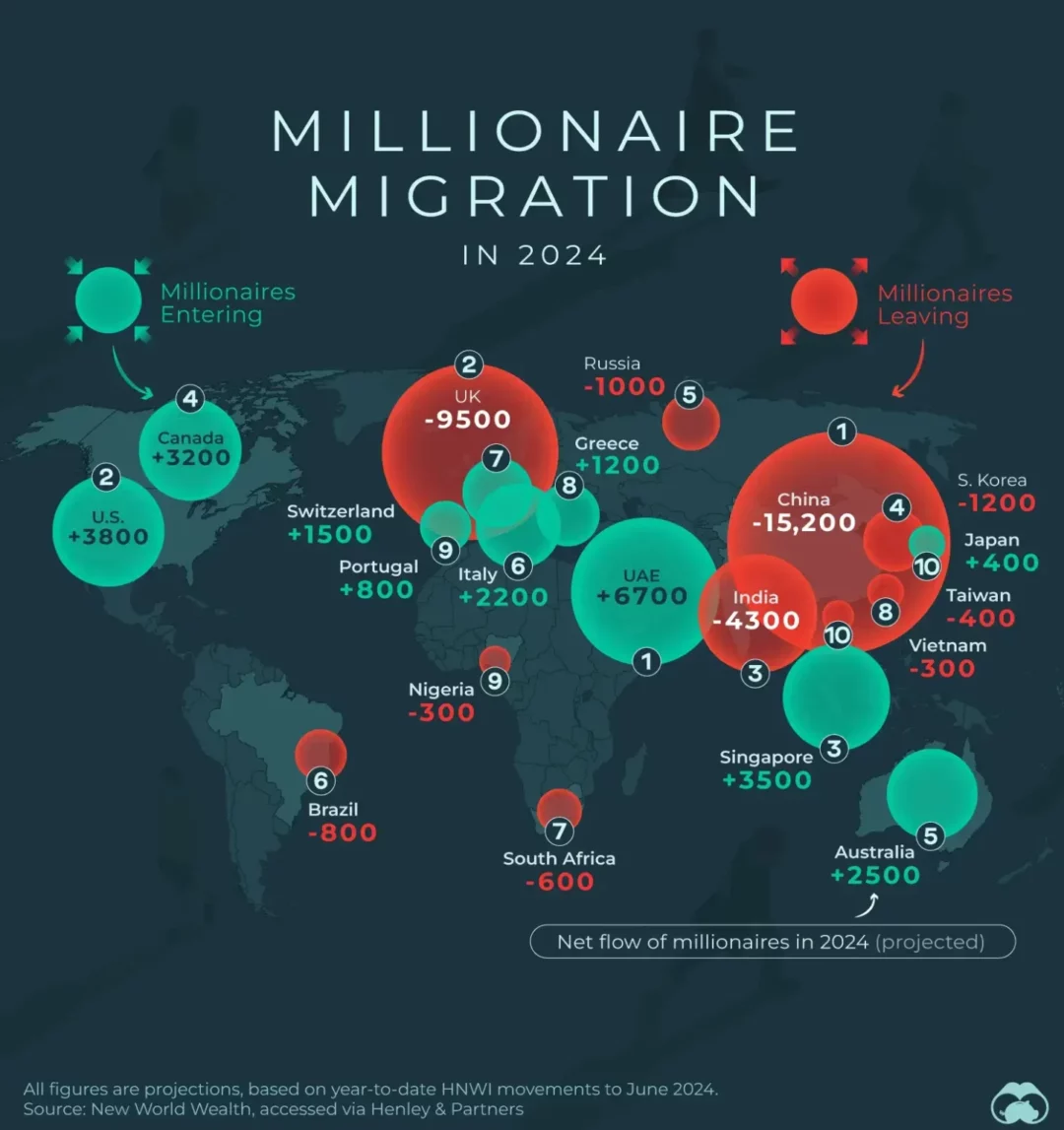

The global wealth landscape is experiencing some earth-shattering shifts in 2024, as revealed by the latest millionaire migration data (see below). Behind this trend, highlighting the significant migration and movement of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), is an intriguing insight into the economic and social factors influencing such movement. Concerning for many closer to home and one of the most stand-out aspects of this data is the considerable exodus of wealthy individuals from the UK.

What Is Causing The Exodus?

In short, the UK is projected to see a net loss of 9,500 millionaires in calendar year 2024, making it one of the top countries experiencing an outflow of affluent residents. Several factors appear to contribute to this migration, including:

- Perceived political instability – although arguably few ‘developed’ nations are entirely immune from this currently (noting France and the US to name a few);

- Economic uncertainty post-Brexit;

- High tax rates and the prospect for ever greater tax rises under an incoming Labour Government, noting the proposal to abolish the ‘non-dom’ regime by both the Conservative and Labour Parties; and

- Perhaps more compellingly, the allure of more stable, tax favourable environments in other jurisdictions, such as Italy, UAE and Switzerland.

For example, jurisdictions like the UAE, with a net influx of 6,700 millionaires, and even the US despite being caught up in potential turbulence with the upcoming presidential election, attracting 3,800, are becoming popular destinations due to their perceived favourable tax regimes and economic opportunities.

I’m Thinking of Leaving – What Do I Do?

Whatever the case may be, migration presents many opportunities as well as many potential pitfalls. For anyone considering such a move, it is essential to understand the complexities involved, particularly when it comes to taxes. When leaving, perhaps predictably so, the focus tends to be on the arrival lounge rather than the departure lounge. Put differently, where the grass appears greener, human attention will follow. However, leaving a country without proper tax advice can lead to unexpected liabilities and headaches. Indeed, leaving may not necessarily mean a total severance with no return as, after many years of residence, it is so easy to say goodbye for good.

So, a key part of relocating is understanding the tax implications in both places. In the UK, for instance, the tax system is residence-based, meaning some might still owe UK taxes even after moving abroad. The nuances of double taxation agreements between the UK and the destination country can also impact the fiscally-felt future lying ahead. So, getting comprehensive tax advice isn’t just a good idea—it’s a must.

Tax aside, the relocation of millionaires can impact the economies of both the countries of departure and arrival. In the UK, losing high-net-worth individuals could affect investment levels, job creation, and overall economic dynamism. On the other hand, countries attracting these wealthy migrants stand to gain significantly, with potential boosts in investment, economic activity, and the prime property market.

Some Parting Advice

Put simply, the millionaire migration trend of 2024 highlights the importance of stability, economic opportunity, and favourable tax policies in retaining and attracting HNWIs to various jurisdictions. As the global wealth landscape continues to evolve, understanding these trends will be crucial for navigating the opportunities and challenges ahead. As ever, contact your friendly tax advisor to understand how such moves might impact you.

For private wealth & tax advice and services, please contact Ben Rosen via our contact form below.

What are the Tax Implications of Gifting a Property?

Properties commonly comprise the majority of an individual’s estate, in value terms, and so reviewing the ownership and implementing changes around property are key aspects of estate planning.

In 2021/22, 2.1 million households reported having at least one second property, and so clients often consider whether to gift their property to reduce the value of their estate and, in doing so, mitigate their potential inheritance tax (IHT) exposure.

This article focuses on the CGT and IHT implications when considering gifting property, particularly in light of the Spring Budget announcement that the top rate of Capital Gains tax (CGT) for higher and additional rate taxpayers is being reduced from 28% to 24%.

Capital Gains Tax

A sale or gift of a property is treated as a disposal for CGT purposes. If any asset is disposed of and there has been an increase in value since the date the asset was acquired, there will likely be a charge to CGT. The amount of CGT is calculated by looking at the difference between the value at the date of acquisition and the value at the date of disposal after allowable deductions such as estate agents and solicitor fees.

There is, however, a potential CGT relief available for individuals on the disposal of their main residence. Principal Private Residence (PPR) exempts, without limit, the full gain on the sale or gift of one’s main residence. The relief is available in full when the property has been an individual’s only or main residence for the entire period of ownership (or all but the final 9 months of ownership).

PPR is also partially available when the residence has, at some point during the ownership, been the main residence, such as if the property has been let out for one or more periods.

In recent news, controversy surrounding the applicability of PPR has come under the spotlight in relation to Labour’s deputy leader, Angela Rayner. Mrs Rayner is reported to have failed to pay CGT on her disposal of her property as she stated it was her main residence. However, for married couples, as in the case of Mrs Rayner, they can only have one principal residence for CGT purposes and if they do own more than one property, they have to choose which is their main residence.

It is, therefore, unclear whether this property was her main residence and if her disposal was, in fact, eligible for PPR.

Individuals should, therefore, carefully consider the potential CGT implications of any disposal.

Capital Gains Tax Rates

From 6 April 2024, the annual exempt amount for CGT purposes is reduced to £3,000 for an individual in each tax year, and the rest of the gain (to the extent there is a gain) is chargeable as follows on residential property:

| Gains on disposals of residential property and carried interest. | |

| Rate for basic rate taxpayers | 18% |

| Rate for higher and additional rate taxpayers | 24% |

Inheritance Tax

A second consideration is the IHT implications of a lifetime gift of property.

As a starting point, IHT is charged at 40% and applies to UK and non-UK residents alike on their ownership of UK situated assets. All individuals, including non-UK residents are entitled to an allowance of £325,000 (known as the nil-rate band) under which IHT is not payable. As such, the rate of tax is 40% insofar as the value of the deceased’s UK assets exceeds the nil-rate band.

The value of a gifted property above the available nil-rate band would likely be considered a potentially exempt transfer (a PET). This means that IHT is not payable on that gift provided the individual who makes the gift survives seven years.

If the individual making the gift were to die within seven years of making the gift of the property, the gift will be pulled back into the estate, and IHT will be payable to the extent it exceeds the nil-rate band. The IHT will either be payable by the persons who received the gift or from your estate at the rate of 40%.

A further consideration is, if a property is gifted and the individual making the gift continues to benefit from the property for example by receiving the rental profits, the gift would be treated as remaining in your estate. This is known as a ‘gift with reservation of benefit’.

Conclusion

In summary, if you are considering making a gift of a property, legal advice should be taken of the potential tax implications of making the gift.

For private wealth & tax advice and services, please contact Eleanor Catling via our contact form below.

UK Immigration Perspective on the New UK Tax Regime

Following the recent Budget announcement, the proposed and radical changes to the tax regime have sparked discourse among professionals within the private wealth space. One of the key impacts is the abolition of the non-dom tax regime, a key attraction for wealthy clients considering residency in the UK. The impact of this change could potentially shake the UK’s competitiveness as a destination for talent and wealth.

Effective from the 6 April 2025, the new tax regime will apply to new arrivals who have lived outside of the UK for a consecutive 10 tax year period. These individuals will benefit from tax relief for a four-year period, allowing them to bring wealth to the UK without incurring additional tax charges. The new regime will also apply to existing UK resident non-doms who have been in the country for four years or less.

Residency Challenges

Whilst the four-year relief period may appear manageable, it poses challenges in alignment with immigration residency requirements. For individuals intending on securing British Citizenship, a continuous UK residence of five years is typically required for settlement, followed by an additional year for citizenship eligibility. This dealignment raises concerns about the practical capability for individuals seeking citizenship under the new regime.

As the UK anticipates elections later this year, the potential for a change in government adds another layer of uncertainty. The implications of a shift in leadership on the newly proposed tax regime remain to be seen, and it underscores the complexity and challenges of the private wealth space.

Next Steps

Our advice to our clients is to consider taking pre-emptive steps to secure your residency in the UK by April 2025. If you are considering obtaining residency in the UK, our team of lawyers can provide you with a strategy together with our tax colleagues to enable you to secure temporary or permanent residency, this is particularly important if you own property in the UK.

If you or your connections require legal advice, please contact Jayesh Jethwa or fill out our enquiry form below.